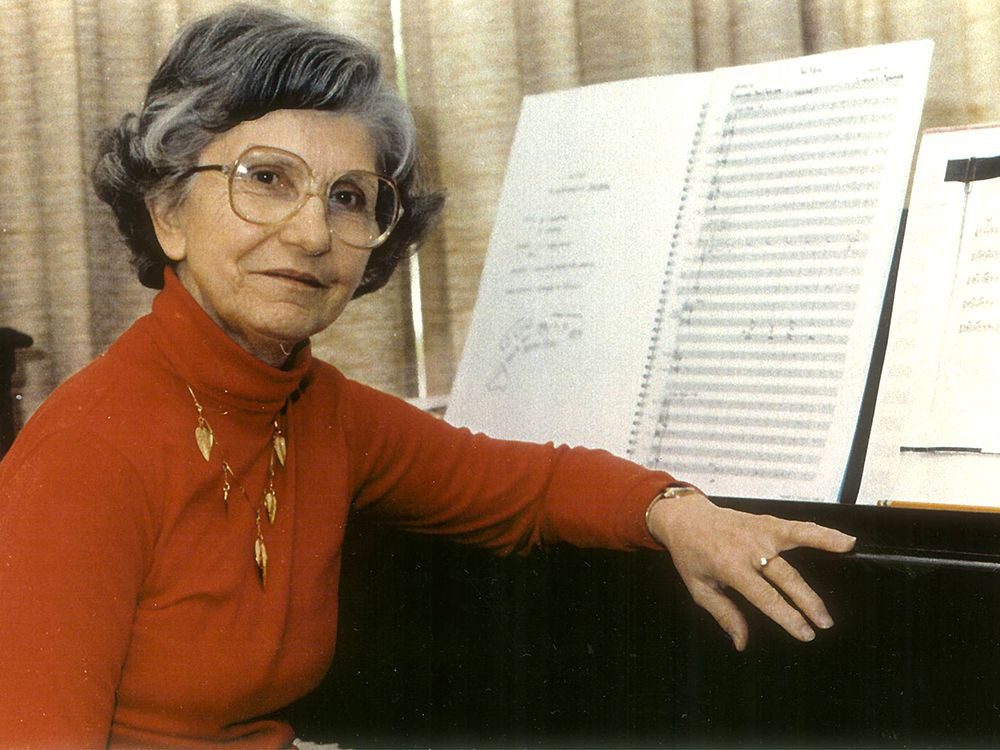

Violet Archer was a remarkable composer, educator, and pianist who made an immense contribution to Canadian music. Her compositions have a way of quickening the pulse and rekindling a zest for life. Archer was widely recognized for her masterful command of both traditional and modern techniques, alongside her incredibly diverse and unparalleled body of work, as reported by iedmonton.net.

Early Life and Musical Beginnings

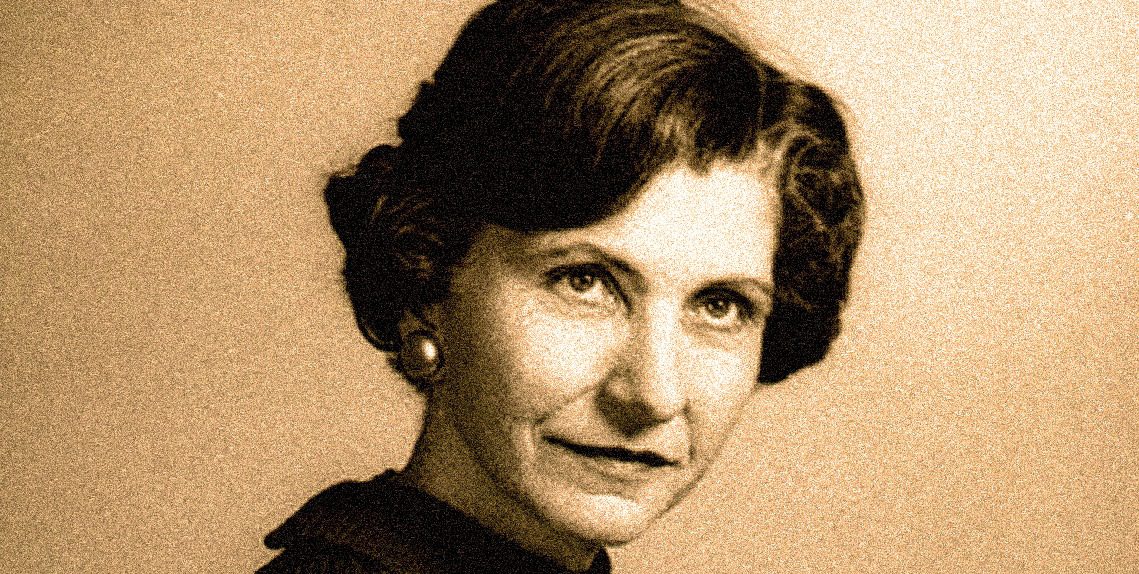

Violet Archer was born in Montreal on April 24, 1913. When she was just 14 months old, her mother moved with her to Italy, where Archer had her first taste of music. This initial experience was reinforced back in Canada by her opera-loving parents. At the age of 10, she began seriously studying piano, and by 1930, she had graduated from the Montreal High School for Girls.

At 17, Violet started working as a répétiteur while simultaneously studying at the McGill Conservatory, where she honed her skills in piano under Dorothy Sherwood and also studied organ. Soon after, Archer began exploring composition on scholarship. In 1934, she earned her Licentiate in Piano from McGill Conservatory, followed by a Bachelor of Music in 1936, and an Associate Diploma from the Royal Canadian College of Organists in 1938.

Archer was also a percussionist in the Montreal Women’s Symphony Orchestra and worked as an accompanist and piano and music theory teacher. For a period, she served as a substitute organist in various Montreal churches. Violet made her compositional debut in 1940 with “Scherzo Sinfonico,” performed by the Montreal Orchestra under Douglas Clarke. In 1941, Adrian Boult began broadcasting her composition “Britannia — A Joyful Overture” to the armed forces in Europe via the BBC. Violet’s first published work was “Habitant Sketches.”

In 1942, Archer journeyed to New York to study with Hungarian composer Béla Bartók, who introduced her to folk melodies and variation techniques, igniting her interest in folk music. He also inspired Violet to explore various modes and rhythms. From 1944 to 1947, she taught at McGill Conservatory while concurrently studying composition at Yale University, learning how to adapt her compositions for specific instruments and work effectively with performers.

In 1948, she earned her Bachelor of Music degree, and a year later, her Master’s. In 1949, she was awarded the Woods Chandler Memorial Prize for her choral-orchestral work “The Bell,” which premiered in 1953. Her “Fanfare and Passacaglia” was first performed at the International Student Symposium on Music in Boston in 1949.

A Distinguished Teaching Career

From 1950 to 1953, Archer served as composer-in-residence at North Texas State College, where she also studied musicology under Otto Kinkeldey. In 1952, she began teaching at Cornell University. Soon after, she became a professor of composition at the University of Oklahoma, where she also hosted radio and television programs dedicated to 20th-century music.

In 1961, after returning to Canada, Archer enrolled in a doctoral program at the University of Toronto but paused her studies to care for her ailing mother. In 1962, she joined the Faculty of Music at the University of Alberta, where she was appointed head of the Department of Music Theory and Composition. It’s worth noting that she remained there until her retirement. She also lectured at the University of Alaska in 1992 and was appointed adjunct professor at Carleton University. Beyond her academic duties, Archer organized Canadian Music Week in Edmonton and served as a juror for various composition competitions. In 1975, Archer was elected to the advisory council for the celebration of women in the arts in Edmonton.

Significant Achievements

A methodical composer, Archer worked within the traditions of Western classical music while also incorporating modernist serial methods, parallelism, and folk influences. Her early works reflect the creative approaches of Douglas Clarke and Ralph Vaughan Williams, often showing a tendency toward chromaticism. While she taught her students 12-tone technique, she never employed it in her own compositions.

Throughout her career, Archer composed over 330 pieces, many of which have been performed in more than 30 countries. In essence, she built an extensive musical foundation covering most vocal and instrumental ensembles, including the comic opera “Sganarelle” (1973), the soundtrack for the documentary “Someone Cares” (1976), and many others. Recognizing the importance of nurturing future musicians and cultivating an audience that understands and appreciates 20th-century harmony, melody, and rhythm, she wrote numerous works for beginner and intermediate performers and encouraged her colleagues to create compositions for children.

Among her early works, Archer’s piano pieces were the most accomplished, but she soon began effectively utilizing the orchestra, particularly after studying the clarinet, percussion, and string instruments. Her expanded skills were fully evident in the Piano Concerto (1956), with its brilliant solo part and a transparent orchestral score featuring prominent wind solos within a rich texture. Performing this composition demands immense virtuosity from both the soloist and the orchestra.

Contrast and strong formal organization are hallmarks of Archer’s compositions. Her interest in the rhythmic freedom of folk music evolved and found abstract expression in her sonatas and String Trio No. 2 (1961). Violet often noted that the Canadian landscape significantly influenced her music. She frequently turned to folk music for inspiration for her compositions. Violet was often inspired by poetry and wrote several song cycles and individual songs using poems by various authors, such as Walt Whitman and Dorothy Livesay, among others.

In the last decade of her life, Violet continued to compose, teach, and travel for the premieres of her works. In 1993, at the age of 80, she became composer-in-residence at the Festival of the Sound and participated in the University of Alaska festival. In 1998, she moved from Edmonton to Ottawa to be closer to family. A year before her passing, Archer completed her final commissioned composition, the Concerto for Accordion and Orchestra. Violet Archer passed away on February 21, 2000.

Colleagues’ Recollections

Dr. Fordyce Pier of the University of Alberta described Archer’s music as characterized by superb craftsmanship and stunning intensity. Cellist Julian Armour also highly praised Violet’s impact, noting that her body of work was phenomenal and almost all of her compositions were wonderfully crafted. He added that for decades, Archer proudly held the title of one of Canada’s most important and influential composers.

Archer is also remembered for her unwavering support of new music, and especially her belief in the importance of creating 20th-century music for young people. Her work is remarkable because she achieved great recognition at a time when it was incredibly difficult for women to become widely recognized composers. Violet was one of three prominent contemporary Canadian female composers.

In 1985, Edmonton hosted a three-day Violet Archer Festival, featuring performances of 14 major works and several premieres by the composer. In 1993, a gala concert was held in Edmonton to celebrate Archer’s 80th birthday. Her departure from Alberta’s capital was marked by a farewell concert. A park in Edmonton was named in Violet’s honour. In 1992, the University of Alberta’s Faculty of Music named a composition scholarship after her. It’s truly difficult to overstate this woman’s contribution to the development of music.